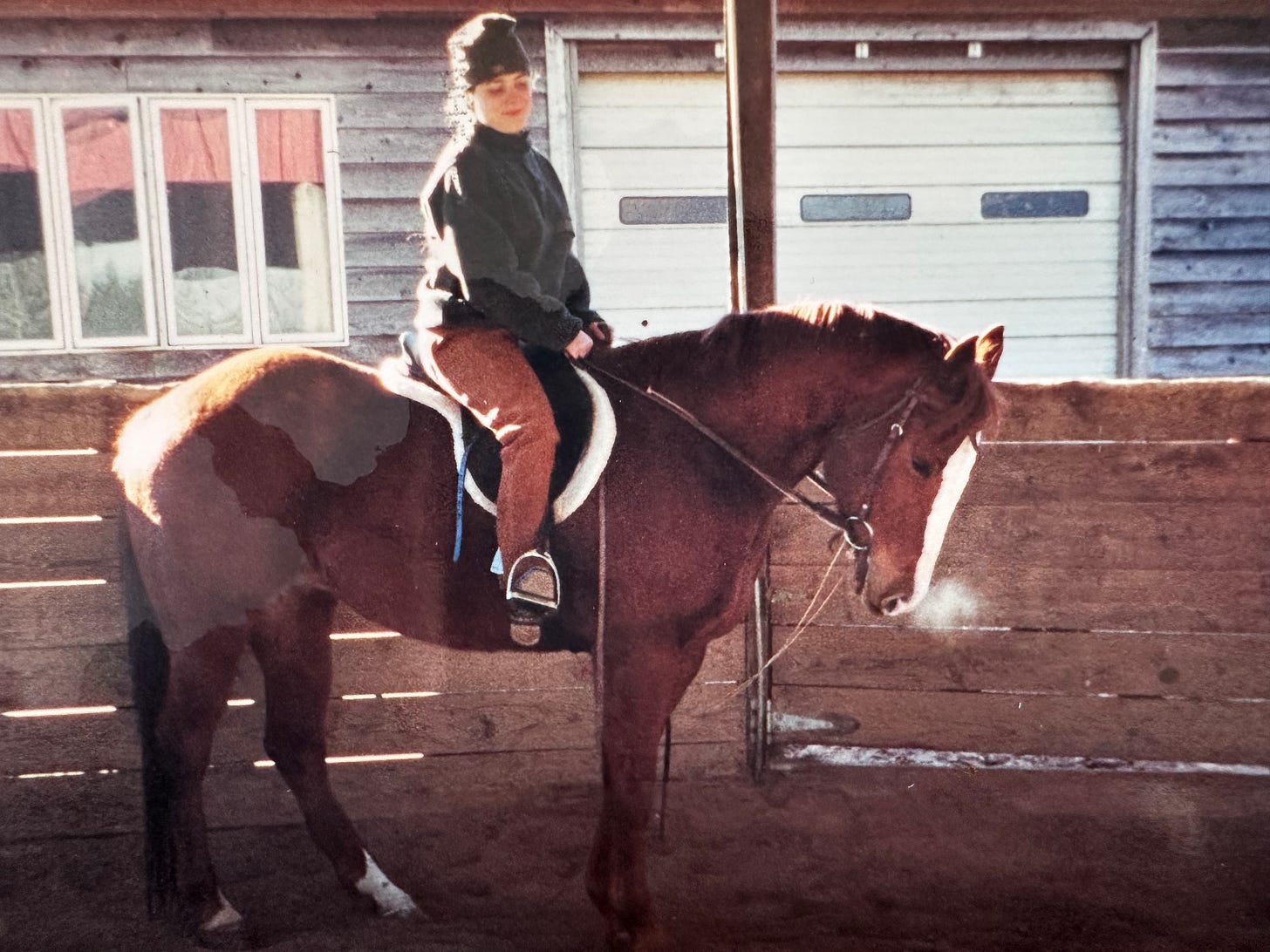

It’s impossible to fit an entire lifetime into a single post, so this week, I’m continuing the celebration of Max’s 30th birthday with a few more remembrances of this little red horse who’s still going strong.

Max’s story is my story.

This essay touches on the divide between the haves and the have-nots. It’s a line that shows up everywhere but especially in the horse world. And when we talk about divides in horsemanship, we inevitably run into the longstanding tension between Western and English traditions. On the surface, it’s a difference in tack and attire but underneath it all, the ideological split goes so much deeper.

The English disciplines were shaped by aristocracy and army officers — fox hunters, cavalrymen, people in formal coats.

The Western disciplines developed from grassroots workers managing cattle and running farms — the people who grow our food.

Max and I have lived in the liminal spaces, borrowing what fit, discarding what didn’t, and figuring out where to go next when the map went blank. It’s a privileged position slithering through worlds like a chameleon and I know that perspective isn’t afforded to everyone. And that, along with so many other reasons, is why I feel compelled to share my stories.

What Max and I have built doesn’t look like tradition but it has held and it has stayed true. The world we’ve brought to life at my farm isn’t controlled by fear. It is formed instead, and keeps being shaped, by learning how to ask better questions.

The shift from control to curiosity changes everything.

Let’s get started.

When the Map Goes Blank

I didn’t have a truck or trailer, so Max and I relied on Tommy Smith to keep us connected to the outside world and to take us to horse shows.

I was raised in the hunter/jumper world where showing was the ultimate goal for every horse. On weekends, Tommy and I pulled into a show grounds before dawn with Max and whoever else we could muster — young horses that needed miles, random boarders in our primarily Western barn, curious to expand their knowledge — all loaded and swaying on a stock trailer.

Tommy was dry and understated, but razor-sharp. While the louder trainers barked from the rail, he set fences and watched, muttering quiet instructions to me as I passed. The antics of the other trainers tickled him. He’d grin across the arena and wait to lock eyes with me before we laughed.

Tommy was a cowboy, but he was right at home in the land of custom tall boots. He fixed the horses that people broke.

In between my rides, he had me stand by the in-gate and take in the rounds of others, quietly ranking the riders 1st to 6th in this hugely subjective sport. Every detail was relevant. Was the judge cranky? Did they prefer a certain color? What direction was the wind blowing? Were the horses spooking at something in the corner? What questions were the jumps asking me to solve?

Tommy taught me to notice details.

“What rider do you like best?”

He saw me watching one in particular, a polished jumper rider guiding a green horse in the lower levels. That rider won the class.

“Find out who he trains with,” Tommy said. “See if that trainer will take you on.”

“But I’m your student.”

“You and I are just messing around,” he said. “It’s time for you to get serious.”

The Cost of Entry

I tracked down the trainer from the show — we’ll call him The Master — and he agreed to take me on as a student if I moved Max to his farm within a few months of starting. I told him that I would move my horse as soon as I was able. I would have promised to buy six horses for the chance to ride with The Master, but secretly I knew I wasn’t moving Max anywhere yet. I still had so much to learn from Tommy and I was still trading stall cleaning for board.

The hunter world sends their broken horses to cowboys like Tommy when they’ve tried everything else. But I didn’t want to just learn how to jump. I wanted to understand what kept horses sound and mentally whole. If you’d asked me then, I wouldn’t have had the words. I just knew my time with Tommy wasn’t finished. My gut said to stay put.

And I was in love with this farm we all shared at the base of the mountain. It held me safely in the cradle of its fields and hills as I figured out how to stand on my own two feet. It was the first place where I felt held while I slowly understood how to hold my own self up.

Tommy had me watching footfalls endlessly between cleaning stalls and throwing hay, watching how the horses moved around us. At first, I could hardly tell the difference between left and right, fore and hind, but under Tommy’s tutelage, I learned to pick out the flick of a fetlock and the angle of a hock. It was like a shutter opening and closing on the horse’s inner life.

I’d watched horses my whole life, but I was only just beginning to see them.

And Tommy saw something in me that was worth investing in.

Eventually, I started making the long drive deeper into the mountains to ride with The Master once a week. The contrast was stark. He drilled my position to a classical standard, while children on ponies circled around me.

There were no shortcuts and no exceptions in The Master’s ring. I learned how our modern jumping position was adopted from the Italian cavalry school in the 1920s, a relatively small leap in our ancient partnership with the horse.

Jumping is something horses do for humans. In the wild, they go around obstacles. They only leap when they must.

The Master studied under military riders from the now-disbanded U.S. Cavalry School at Fort Riley. It was the same school that brought us the modern riding seat and created the industry we now know as hunters. Those military traditions condensed and brewed in this little pocket of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Everything I was learning came from traditions built for war.

In the world of upper level English riding, performance trumps emotion in both horse and rider. You do what you’re told and ask questions later — if at all. I had to prove my worth to The Master to earn the privilege of his time and care. This way of being and working was familiar to me, a language of posture and exchange that I had grown up with in my home and also in the horse world.

The more I rode with The Master, the easier it became to overlook the value of Tommy’s knowledge because he offered it so freely, no strings attached. I’d never had to earn Tommy’s time or prove myself worthy of his knowledge. He just showed me what he knew. I began to mistake cost for value.

It would be a very long time and some brutal heartbreak before I was able to see past the smokescreen of privilege and understand what was really valuable. Like how an expert spots the difference of a manufactured diamond, knowledge and practice happens with time and study.

Even the Ground Gives Warnings

I only took Max with me a few times in the years I rode for The Master. One memorable lesson, Max kept tripping in the same flat section of the beautifully maintained, pristine footing every time we passed a certain section of the ring.

We shared the arena with a visiting German rider schooling a chunky, young pony.

At one point, Max tripped so hard for no reason that he stumbled and bonked his nose on the ground.

He immediately righted himself and kept on like nothing happened, but the momentary scrabbling commotion of his grunting to gain his footing shocked the young pony traveling in front of us and the German rider struggled to keep from falling as her creature took off in fright.

Max kept trotting at a quiet pace, unconcerned and unbothered by his part in the explosion. He shook it off and kept going.

But, he stumbled a little when we passed the same spot in the ring again.

We all need a friend like Max.

Most of the time in my weekly sojourns to ride with The Master, my task was to look pretty and figure out the puzzle that the day’s horse selection offered.

At The Master’s farm, horses came and went from Europe. The last of the old money, American equestrian families, like the Budweisers, were dispersing their breeding herds and the new money scions of society were buying horses and vying to take their place.

The Master’s farm was the epicenter of a this changing of guard. After I proved myself, I entered a golden window of favor. His name became a ticket. My association with him didn’t just open closed doors — it revealed doors I hadn’t even known were there.

The elite, moneyed circles of horse sport have always been a place of shadows, spectacle, and mysteries. From old novels to modern conspiracies, the old guard retains its mystique and the world watches like commoners at the Kentucky Derby catching a glimpse of the grand hats in the stands.

It’s a world built on the backs of outcasts and misfits, all laboring to keep the fantasy alive and the farms running.

I’m thankful for the time I spent chasing that fascination because without the glimpse, I’d still be in love with the mystery.

In those shuttered rooms lined with rugs steeped in the musk of history I learned that blood takes the same path from all our wounds. I saw that breeding, in horses and in humans, ought to consider intelligence before trying to replicate strength.

Because honestly, how do we even decide what’s beautiful? Who taught us to want the things we want?

Max and I lived two lives.

One followed footfalls with Tommy Smith, a mentor who let me think.

The other obeyed The Master, who taught me not to question the work.

At home, I took what I’d learned from The Master and turned it on Max. I feared he wasn’t good enough. I pushed his body into frames that looked acceptable. I used every trick and gimmick to make him fit.

I did the same to myself.

“You’re going to get hurt,” Tommy warmed in an uncharacteristic moment of directness.

“I know what I’m doing,” I said, sliding draw reins through the rings of a bit. Draw reins work like a pulley and wench, but on a horse the device leverages pressure, amplifying it to force the horse’s head down.

“We’ll see,” Tommy said.

As he wandered away from the arena, I dug in and got to work.

Field Notes

Max is 30 years old this year. He is still here, and he’s sound in body, mind, and spirit, but he remains that way in spite of the hard lessons it took for me to notice his worth. I didn’t shape him with ambition, but he waited for me to tear things down and build them back up again.

I look at him now and see every version of myself that once thought I had something to prove. But what Max has always known (what I am still learning) is that horses are not our mirrors or our trophies. They’re our partners in discovering the roads that lead to our best selves — if we let them.

Max and I are still going places, but we’re moving differently now.

And the questions are better.

Max and I will be back next week with more stories.

Love,

Kim

They are our partners on the roads that lead to our best selves. Amen. ❤️🐴❤️

Art, no matter the medium, helps us see things in a different light. Great art helps us see ourselves minus delusion. This is great art.